SL Helicopter Flying Handbook/Advanced Flight Maneuvers

SECTION 9. Advanced Flight Maneuvers

Contents

1 Reconnaissance Procedures

Reconnaissance procedures are used to gather more information about an unfamiliar site, particularly an off-airport site, before attempting a landing.

1.1 High Reconnaissance

The goal of high reconnaissance is to gather information about a site including wind direction and speed, identify a suitable touchdown site, identify a suitable approach path and suitable abort paths, and identify any obstacles in the area that might present a hazard. The pilot should also consider potential emergency landing spots in the event of an engine failure during the approach.

High reconnaissance should be conducted at high enough altitude to have a good view of the planned landing area, as well as be able to make an emergency landing in the event of an emergency. Fly a circular path around the planned landing area that is at about a 45 degree angle from the helicopter (see SECTION 8. Basic Flight Maneuvers - Turns_Around_a_Point). Evaluate the landing area during the maneuver, but do not become so focused on the landing area that you lose situational awareness on the aircraft.

1.2 Low Reconnaissance

A low reconnaissance is performed on the approach to the landing area. Continue to evaluate the suitability of the area, and look for anything you may have missed during the high reconnaissance. If the pilot determines that the area is safe, the approach can be continued to landing. However, any decision to abort should be made before the helicopter goes below ETL.

If a decision to land has been made, terminate the approach in a hover. Carefully evaluate the suitability of the surface as you set down, and keep the helicopter at full operating RPM until sure that the surface is secure. Once the pilot is sure that the helicopter is stable, a normal shutdown can be conducted.

1.3 Ground Reconnaissance

Prior to departing an unfamiliar location, the pilot should carefully analyze the surrounding area. Identify the best departure path, and make note of any hazards in the area. Consider the direction and speed of the wind, any obstacles, the weight and expected takeoff performance of the aircraft and any obstacles. Also consider the surface area and any nearby hazards that may come into contact with the tail rotor during pick up.

2 Maximum Performance Takeoffs

A maximum performance takeoff is a takeoff at a steeper than normal angle so as to be able to clear nearby obstacles. It can be used when departing from a small confined area. While in some cases a vertical takeoff may be necessary, it should be avoided when possible so as to reduce the risk due to a potential engine failure during the maneuver.

Before attempting the technique, reposition the helicopter in a hover to the most downwind area to maximize the available takeoff path. Bring the helicopter and note the available power by checking difference between the power required the hover, and the maximum available power as indicated by the red line on the manifold pressure gauge (for piston helicopters), or torque gauge (for turbine helicopters). Orient the helicopter in the direction of departure, and set back down before beginning the takeoff.

Use the following procedure for the takeoff:

- Begin by pulling collective to get the helicopter light on the skids. Neutralize any drift or rotation with cyclic and pedals.

- Smoothly continue to pull collective, and pitch forward with cyclic for a 40-knot attitude.

- Continue to raise collective until the maximum available power is reached (red line on the manifold pressure or torque gauge).

- Use cyclic as necessary to control the flight path, while monitoring rotor RPM to ensure that it does not drop.

- Once the obstacle has been cleared (or at 50 feet, when conducting the maneuver as a training exercise), reduce collective and resume a normal climb.

If it becomes clear that the helicopter will not clear the obstacle, abort the procedure, and land back at the starting location.

Common Errors

- Failure to consider aircraft performance capabilities

- Nose too low on pickup resulting in forward speed too quickly

- Failure to maintain rotor RPM

- Abrupt control movements

- Failure to resume normal climb after clearing the obstacle

3 Running/Rolling Takeoff

A running takeoff with skids or wheels is sometimes performed when the aircraft is heavily loaded, or high density altitude conditions prevent a sustained hover. Avoid a running takeoff if the helicopter cannot be hovered at least momentarily. If the helicopter cannot lift off at all, then there may not be sufficient power for this maneuver.

Begin the maneuver by aligning the helicopter with the takeoff path. Next increase collective until helicopter becomes light on the skids. Then push the cyclic slightly forward of neutral and apply just a touch more collective so that the helicopter begins to slide across the surface. As the helicopter begins to move, use pedals to steer so as to maintain a straight path. As the helicopter passes through ETL, it should naturally transition into a climb. Climb out as normal once breaking from the ground, being sure to maintain speed above ETL.

The maneuver may be practiced by selecting a power limit (manifold pressure or torque) beyond which collective will not be pulled. Attempt to complete the power without exceeding that limit.

Common Errors

- Failing to align heading and ground track to minimize surface friction

- Attempting to become airborne before reaching ETL

- Using too much forward cyclic during surface run

- Using too aggressive cyclic after breaking from the ground

4 Rapid Deceleration or Quick-Stop

The quick-stop is a maneuver to quickly bring the helicopter to a stop from forward flight. It can be used to abort a takeoff in the event an obstacle is observed during a takeoff, or to simple terminate an air taxi. Quick-stops are normally practiced over a taxiway or runway, away from other traffic.

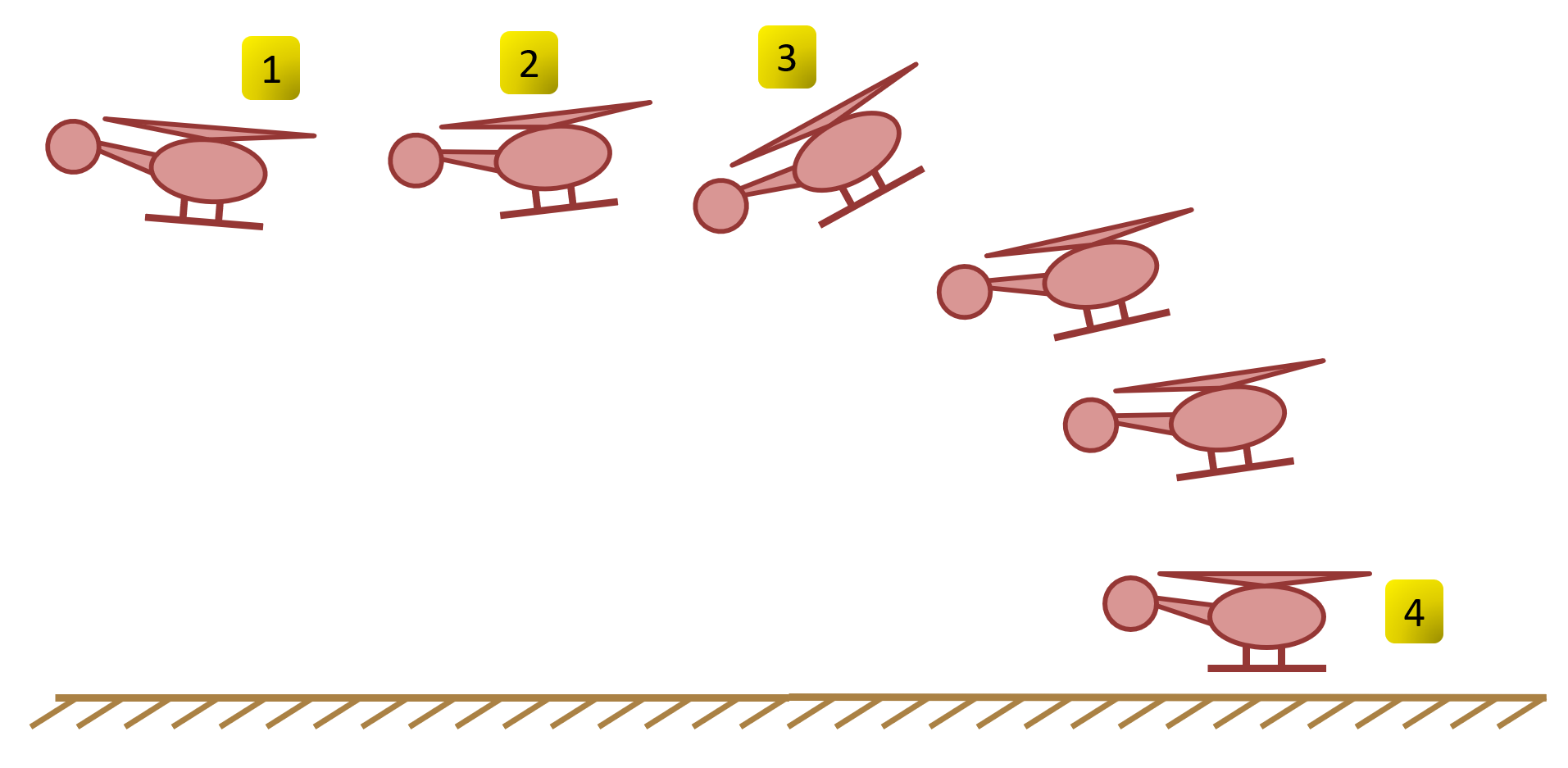

A quick-stop requires careful coordination of all flight controls. It should be practiced at a safe enough height to have adequate clearance between the ground and the tail rotor. When practicing the maneuver use an air taxi height of 20 to 50 feet, and a forward speed of about 50 knots. Then follow the following technique as shown in the Figure 1:

- Begin by applying smooth aft cyclic simultaneous with down collective to avoid ballooning when you pull the cyclic back. Apply right pedal as necessary to prevent any yaw as you reduce collective.

- As the helicopter slows continue adding aft cyclic and down collective.

- As the helicopter nears a stop, begin to level the helicopter, and apply up collective as necessary to slow the descent.

- Bring the helicopter to a stationary hover once completely stopped.

Common Errors

- Initiating the maneuver by lowering the collective without aft cyclic

- Applying aft cyclic too quickly or without down collective allowing the helicopter to balloon

- Failing to keep the aircraft aligned with direction of travel with pedals

- Allowing helicopter to stop with an excessively tail low attitude

- Failing to maintain rotor RPM

- Failing to use the collective after stopping forward speed and allowing the helicopter to descend too rapidly

5 Steep Approaches

A steep approach can be used when landing is to a confined area, and obstacles in the area may prevent a normal approach. A steep approach is normally conducted at a 13º to 15º angle.

The procedure is essentially the same as for a normal landing, except you should slow to approximately 30 knots and maintain the speed through the descent. Care must be taken not to allow the conditions for vortex ring state to develop. In particular, do not let the airspeed drop below 30 knots until landing is assured.

In some aircraft, the landing point may not be visible due to the steepness of the approach. The pilot must learn to use additional cues to help them gauge the landing point.

Common Errors

- Failing to maintain RPM throughout the maneuver

- Improperly using collective to maintain angle of descent

- Failing to make pedal adjustments to compensate for collective changes

- Slowing airspeed excessively to avoid overshooting and going below ETL while still at altitude

- Using too much aft cyclic near the surface which may result in a tail strike

6 Shallow Approach and Run-on Landings

In SECTION 8. Basic Flight Maneuvers - Landings_to_the_Surface, a technique for landing in full hover power was unavailable was introduced. In that maneuver, the pilot lands directly to the surface without entering a stabilized hover. However, that technique still requires going below ETL while still in the air. In some cases, the density altitude or power available may make even that inadvisable. In such cases, a better approach would be a run-on landing. In a run-on landing, the pilot approaches as a shallower than usual angle, and allows the helicopter to contact the surface while still above ETL.

Use the following procedure:

- Begin the maneuver at a lower altitude with a shallower angle (3 to 5 degrees) than would be used in a normal approach.

- Maintain heading with pedals

- As you approach the touchdown point, gradually reduce the approach speed with back cyclic and the descent rate with up collective, but do not go below 30 knots.

- Level the helicopter right before touchdown and make contact with skids parallel to the direction of movement at about 30 knots.

- Maintain directional control on the ground with pedals, slowly reducing the collective until helicopter comes to a stop

- Lower collective fully once helicopter stops.

When practicing this maneuver, choose a maximum power (manifold pressure or torque) beyond which you will not pull more collective.

Common Errors

- Using excessive nose up attitude near surface to slow helicopter

- Using insufficient collective to cushion the landing

- Failing to maintain proper heading

- Touching down at an excessive speed

- Touching down after slowing below ETL

- Lowering collective to rapidly after touching down

- Failure to maintain proper rotor RPM

7 Slope Landings

While a flat surface is always preferred, there may be times when the pilot is forced to choose to land on a sloped surface. For this reason, pilots should practice and be familiar with slope landings.

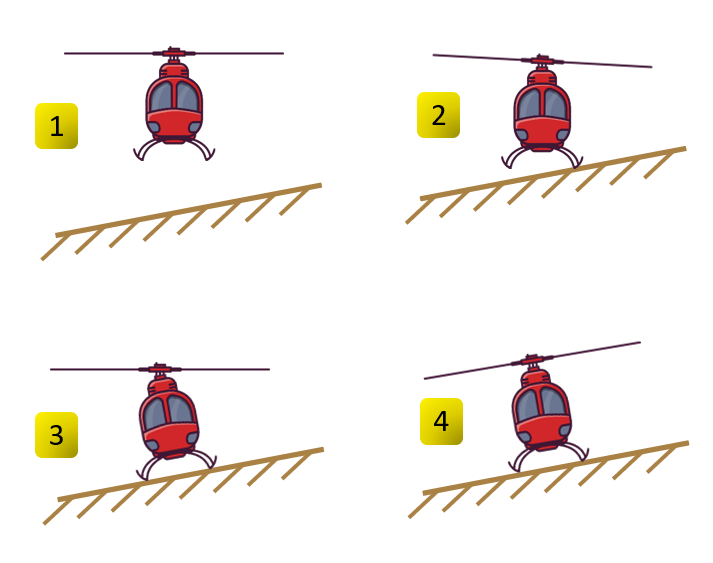

Slope landings (see Figure 2) should be conducted with the helicopter parallel to the slope. Approach the slope in a forward hover at a 45 degree angle, then do a pedal turn to orient the helicopter parallel to the slope (Position 1). Be careful not to turn the tail rotor toward the slope. Once in a stabilized hover, slowly lower the collective to bring the helicopter down until the uphill skid is just touching (Position 2). Continue to slowly lower the collective, while simultaneously adding gradual cyclic into the slope until both skids are on the ground (Position 3). Once the collective is full down, return the cyclic to the neutral position.

A takeoff from a slop is the same procedure in reverse. Begin by applying cyclic into the slope (Position 3). Gradually increase collective and decreases the amount of sideward cyclic as the downhill skid comes up. Once the helicopter is level with the uphill skid just touching the slope (Position 2), the cyclic should be in the neutral position. Continue to raise collective until the helicopter is in a hover over the slope (Position 1). Move the helicopter sideways away from the slope, and when turning away be careful not to turn the tail rotor toward the slope.

Common Errors

- Failure to maintain RPM throughout the maneuver

- Turning the helicopter tail toward the slope

- Failure to align the helicopter parallel to the slope

- Lowering the down slope skid too quickly

- Using too much, or not enough sideways cyclic toward the slope

- Failing to abort the maneuver if the slope is too steep

8 Confined Area Operations

A confined area is an area in which portions of the approach are obstructed to to terrain or obstacles in the vicinity. This could be a clearing in the woods, or an urban area with buildings. It is the responsibility of the pilot to evaluate the safety of an area before landing. The pilot should consider the suitability of the terrain, any obstacles in the vicinity, wind direction, and suitable approach and departure paths. Also keep in mind it is often possible to land in a location from which a safe departure cannot be made. Be sure you will be able to depart again before landing in an area.

Many of the elements of confined area operations have been discussed earlier in this section. When landing, begin with a high reconnaissance to survey the area and evaluate its suitability. After determining an approach path, continue with a low reconnaissance on the approach which will often be a steep approach. Try to select an approach path that is into the wind and choose the far end of the field as your planned touchdown point to maximize the obstacle clearance on the approach.

When departing, try to depart from the most downwind edge of the area along the departure path. This will maximize the distance before reaching any obstacles to be cleared. You can use maximum performance takeoff techniques as well.

Common Errors

- Failure to perform proper high and low reconnaissance.

- Approach that is too steep or too shallow for the conditions

- Failing to maintain RPM

- Failure to consider alternative emergency landing sites

- Failure to maintain safe clearance from obstacles

9 Pinnacle and Ridgeline Operations

A pinnacle is an area that drops away rapidly on all sides. A ridgeline is an area that drops away rapidly on one more more sides. As always, takeoff and landings should be performed into the wind when possible, but there are several additional considerations.

9.1 Landings

Since the pinnacle or ridgeline is higher than the surrounding area, it can be more difficult to judge your groundspeed on approach. Additionally, once pass below ETL, the pilot must sure they have enough speed and momentum to carry the helicopter to the landing site. When possible, land along the longest dimension of the pinnacle and aim for the far end. When the pinnacle is a man-made structure such as a helipad, ensure that the tail rotor is not intruding on the path along which personnel will be approaching the aircraft.

After touchdown, the pilot should also perform a stability check to make sure the helicopter is firmly on the landing site. Lower the collective slowly, and watch for any movement of the helicopter. If movement is detected, pick up the helicopter and reposition to a different location.

9.2 Take-Offs

When departing a pinnacle, quickly gaining airspeed should be favored over altitude. Since ground effect will be lost as soon as you clear the pinnacle, there can be a tendency for the helicopter to drop if airspeed is not gained quickly enough. This can result in a tail rotor strike if the pilot is not careful. This risk increases greatly when a downwind departure is attempted.